Tuesday, December 23, 2008

Mumia update

On Friday, Dec. 19, 2008, death-row journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal filed his appeal to the US Supreme Court, asking it to consider his case for a new guilt-phase trial. One month before, the Philadelphia DA filed its separate appeal to the court asking to have Abu-Jamal executed without a new sentencing-phase trial. Both are appealing the March 27, 2008 rulings by the US Third Circuit Court.

For more links, videos, photos, etc. go here or go to Abu-Jamal News

In this holiday season of thanks and light, let us remember everyone who is incarcerated and everyone whose loved ones are locked up.

Monday, December 22, 2008

Angela Davis ... oh Angela Davis

Still can't believe I got to hear her speak in person...

Here is an old conversation between her and Dylan Rodriguez from History is a Weapon:

The Challenge of Prison Abolition: A Conversation

Angela: The time I spent in jail was both an outcome of my work on prison issues and a profound influence on my subsequent trajectory as a prison activist. When I was arrested in the summer of 1970 in connection with my involvement in the campaign to free George Jackson and the Soledad Brothers, I was one of many activists who had been previously active in defense movements. In editing the anthology, If They Come in the Morning (1971) while I was in jail, Bettina Aptheker and I attempted to draw upon the organizing and legal experiences associated with a vast number of contemporary campaigns to free political prisoners. The most important lessons emanating from those campaigns, we thought, demonstrated the need to examine the overall role of the prison system, especially its class and racial character. There was a relationship, as George Jackson had insisted, between the rising numbers of political prisoners and the imprisonment of increasing numbers of poor people of color. If prison was the state-sanctioned destination for activists such as myself, it was also used as a surrogate solution to social problems associated with poverty and racism. Although imprisonment was equated with rehabilitation in the dominant discourse at that time, it was obvious to us that its primary purpose was repression. Along with other radical activists of that era, we thus began to explore what it might mean to combine our call for the freedom of political prisoners with an embryonic call for the abolition of prisons. Of course we had not yet thought through all of the implications of such a position, but today it seems that what was viewed at that time as political naivete, the untheorized and utopian impulses of young people trying to be revolutionary, foreshadowed what was to become, at the turn of the century, the important project of critically examining the political economy of a prison system, whose unrestrained growth urgently needs to be reversed.

Dylan: What interests me is the manner in which your trial -- and the rather widespread social movement that enveloped it, along with other political trials -- enabled a wide variety of activists to articulate a radical critique of U.S. jurisprudence and imprisonment. The strategic framing of yours and others' individual political biographies within a broader set of social and historical forces -- state violence, racism, white supremacy, patriarchy, the growth and transformation of U.S. capitalism -- disrupted the logic of the criminal justice apparatus in a fundamental way. Turning attention away from conventional notions of "crime" as isolated, individual instances of misbehavior necessitated a basic questioning of the conditions that cast "criminality" as a convenient political rationale for the warehousing of large numbers of poor, disenfranchised, and displaced black people and other people of color. Many activists are now referring to imprisonment as a new form of slavery, refocusing attention on the historical function of the 13th Amendment in reconstructing enslavement as a punishment reserved for those "duly convicted." Yet, when we look more closely at the emergence of the prison-industrial complex, the language of enslavement fails to the extent that it relies on the category of forced labor as its basic premise. People frequently forget that the majority of imprisoned people are not workers, and that work is itself made available only as a "privilege" for the most favored prisoners. The logic of the prison-industrial complex is closer to what you, George Jackson, and others were forecasting back then as mass containment, the effective elimination of large numbers of (poor, black) people from the realm of civil society. Yet, the current social impact of the prison-industrial complex must have been virtually unfathomable 30 years ago. One could make the argument that the growth of this massive structure has met or exceeded the most ominous forecasts of people who, at that time, could barely have imagined that at the turn of the century two million people would be encased in a prison regime that is far more sophisticated and repressive than it was at the onset of Nixon's presidency, when about 150,000 people were imprisoned nationally in decrepit, overcrowded buildings. So in a sense, your response to the first question echoes the essential truth of what was being dismissed, in your words, as the paranoid "political naivete" of young radical activists in the early 1970s. I think we might even consider the formation of prison abolitionism as a logical response to this new human warehousing strategy. In this vein, could you give a basic summary of the fundamental principles underlying the contemporary prison abolitionist movement?

Angela: First of all, I must say that I would hesitate to characterize the contemporary prison abolition movement as a homogeneous and united international effort to displace the institution of the prison. For example, the International Conference on Penal Abolition (ICOPA), which periodically brings scholars and activists together from Europe, South America, Australia, Africa, and North America, reveals the varied nature of this movement. Dorsey Nunn, former prisoner and longtime activist, has a longer history of involvement with ICOPA than I do since he attended the conference in New Zealand three years ago. My first direct contact with ICOPA was this past May, when I attended the Toronto gathering.

Dylan: Was there anything about ICOPA that particularly impressed you?

Angela: The ICOPA conference in Toronto revealed some of the major strengths and weaknesses of the abolitionist movement. First of all, despite the rather homogenous character of their circle, they have managed to keep the notion of abolitionism alive precisely at a time when developing radical alternatives to the prison-industrial complex is becoming a necessity. That is to say, abolitionism should not now be considered an unrealizable utopian dream, but rather the only possible way to halt the further transnational development of prison industries. That ICOPA claims supporters in Europe and Latin America is an indication of what is possible. However, the racial homogeneity of ICOPA, and the related failure to incorporate an analysis of race into the theoretical framework of their version of abolitionism, is a major weakness. The conference demonstrated that while faith-based approaches to the abolition of penal systems can be quite powerful, organizing strategies must go much further. We need to develop and popularize the kinds of analyses that explain why people of color predominate in prison populations throughout the world and how this structural racism is linked to the globalization of capital.

Dylan: Yes, I found that the political vision of ICOPA was extraordinarily limited, especially considering its professed commitment to a more radical abolitionist analysis and program. This undoubtedly had a lot to do with the underlying racism of the organization itself, which was reflected in the language of some of the conference resolutions: "We support all transformative measures which enable us to live better in community with those we as a society find most difficult, and most consistently marginalize or exclude" (emphasis added)1. A major figure in ICOPA even accused a small group of people of color in attendance of being "racist" when they attempted to constructively criticize the overwhelming white homogeneity of the conference and the need for creative strategies to engage communities of color in such an important political discussion. Several black student-activists I met at ICOPA told me how alienated they felt at the conference, especially when they realized that the ICOPA organizers had never attempted to contact the Toronto-based organizations with which these student-activists were working: a major black anti-police-brutality coalition, a black prisoner support organization, etc. So I certainly share your frustrations with ICOPA. At the same time, I find myself wondering how a new political formation of prison abolitionism can form in such a reactionary national and global climate. You have been involved with a variety of prison movements for the last 30 years, so maybe you can help me out. How do you think about this new political challenge within a broader historical perspective?

Angela: There are multiple histories of prison abolition. The Scandinavian scholar/activist Thomas Mathieson first published his germinal text, The Politics of Abolition, in 1974, when activist movements were calling for the disestablishment of prisons -- in the aftermath of the Attica Rebellion and prison uprisings throughout Europe. He was concerned with transforming prison reform movements into more radical movements to abolish prisons as the major institutions of punishment. There was a pattern of decarceration in the Netherlands until the mid-1980s, which seemed to establish the Dutch system as a model prison system, and the later rise in prison construction and the expansion of the incarcerated population has served to stimulate abolitionist ideas. Criminologist Willem de Haan published a book in 1990 entitled The Politics of Redress: Crime, Punishment, and Penal Abolition. One of the most interesting texts, from the point of view of U.S. activist history is Fay Honey Knopp's volume Instead of Prison: A Handbook for Prison Abolitionists, which was published in 1976, with funding from the American Friends. This handbook points out the contradictory relationship between imprisonment and an "enlightened, free society." Prison abolition, like the abolition of slavery, is a long-range goal and the handbook argues that an abolitionist approach requires an analysis of "crime" that links it with social structures, as opposed to individual pathology, as well as "anticrime" strategies that focus on the provision of social resources. Of course, there are many versions of prison abolitionism -- including those that propose to abolish punishment altogether and replace it with reconciliatory responses to criminal acts. In my opinion, the most powerful relevance of abolitionist theory and practice today resides in the fact that without a radical position vis-a-vis the rapidly expanding prison system, prison architecture, prison surveillance, and prison system corporatization, prison culture, with all its racist and totalitarian implications, will continue not only to claim ever increasing numbers of people of color, but also to shape social relations more generally in our society. Prison needs to be abolished as the dominant mode of addressing social problems that are better solved by other institutions and other means. The call for prison abolition urges us to imagine and strive for a very different social landscape.

Dylan: I think you make a subtle but important point here: prison and penal abolition imply an analysis of society that illuminates the repressive logic, as well as the fascistic historical trajectory, of the prison's growth as a social and industrial institution. Theoretically and politically, this "radical position," as you call it, introduces a new set of questions that does not necessarily advocate a pragmatic "alternative" or a concrete and immediate "solution" to what currently exists. In fact, I think this is an entirely appropriate position to assume when dealing with a policing and jurisprudence system that inherently disallows the asking of such fundamental questions as: Why are some lives considered more disposable than others under the weight of police policy and criminal law? How have we arrived at a place where killing is valorized and defended when it is organized by the state -- I'm thinking about the street lynchings of Diallo and Dorismond in New York City, the bombing of the MOVE organization in Philadelphia in 1985, the ongoing bombing of Iraqi civilians by the United States -- yet viciously avenged (by the state) when committed by isolated individuals? Why have we come to associate community safety and personal security with the degree to which the state exercises violence through policing and criminal justice? You've written elsewhere that the primary challenge for penal abolitionists in the United States is to construct a political language and theoretical discourse that disarticulates crime from punishment. In a sense, this implies a principled refusal to pander to the typically pragmatist impulse to demand absolute answers and solutions right now to a problem that has deep roots in the social formation of the United States since the 1960s. I think your open-ended conception of prison abolition also allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the prison-industrial complex as a set of institutional and political relationships that extend well beyond the walls of the prison proper. So in a sense, prison abolition is itself a broader critique of society. This brings me to the next question: What are the most crucial distinctions between the political commitments and agendas of prison reformists and those of prison abolitionists?

Angela: The seemingly unbreakable link between prison reform and prison development -- referred to by Foucault in his analysis of prison history -- has created a situation in which progress in prison reform has tended to render the prison more impermeable to change and has resulted in bigger, and what are considered "better," prisons. The most difficult question for advocates of prison abolition is how to establish a balance between reforms that are clearly necessary to safeguard the lives of prisoners and those strategies designed to promote the eventual abolition of prisons as the dominant mode of punishment. In other words, I do not think that there is a strict dividing line between reform and abolition. For example, it would be utterly absurd for a radical prison activist to refuse to support the demand for better health care inside Valley State, California's largest women's prison, under the pretext that such reforms would make the prison a more viable institution. Demands for improved health care, including protection from sexual abuse and challenges to the myriad ways in which prisons violate prisoners' human rights, can be integrated into an abolitionist context that elaborates specific decarceration strategies and helps to develop a popular discourse on the need to shift resources from punishment to education, housing, health care, and other public resources and services.

Dylan: Speaking of developing a popular discourse, the Critical Resistance gathering in September 1998 seemed to pull together an incredibly wide array of prison activists -- cultural workers, prisoner support and legal advocates, former prisoners, radical teachers, all kinds of researchers, progressive policy scholars and criminologists, and many others. Although you were quite clear in the conference's opening plenary session that the purpose of Critical Resistance was to encourage people to imagine radical strategies for a sustained prison abolition campaign, it was clear to me that only a few people took this dimension of the conference seriously. That is, it seemed convenient for people to rejoice at the unprecedented level of participation in this presumably "radical" prison activist gathering, but the level of analysis and political discussion generally failed to embrace the creative challenge of formulating new ways to link existing activism to a larger abolitionist agenda. People were generally more interested in developing an analysis of the prison-industrial complex that incorporated the local work that they were involved in, which I think is an important practical connection to make. At the same time, I think there is an inherent danger in conflating militant reform and human rights strategies with the underlying logic of anti-prison radicalism, which conceives of the ultimate eradication of the prison as a site of state violence and social repression. What is required, at least in part, is a new vernacular that enables this kind of political dream. How does prison abolition necessitate new political language, teachings, and organizing strategies? How could these strategies help to educate and organize people inside and outside the prison for abolition?

Angela: In order to imagine a world without prisons -- or at least a social landscape no longer dominated by the prison -- a new popular vocabulary will have to replace the current language, which articulates crime and punishment in such a way that we cannot think about a society without crime except as a society in which all the criminals are imprisoned. Thus, one of the first challenges is to be able to talk about the many ways in which punishment is linked to poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia, and other modes of dominance. In the university, the emergence of the interdisciplinary field of prison studies can help to trouble the prevailing criminology discourses that shape public policy as well as popular ideas about the permanence of prisons. At the high school level, new curricula can also be developed that encourage critical thinking about the role of punishment. Community organizations can also play a role in urging people to link their demands for better schools, for example, to a reduction of prison spending.

Dylan: Your last comment suggests that we need to rupture the ideological structures embodied by the rise of the prison-industrial complex. How does prison abolition force us to rethink common assumptions about jurisprudence, in particular "criminal justice?"

Angela: Since the invention of the prison as punishment in Western society during the late 1700s, criminal justice systems have so thoroughly depended on imprisonment that we have lost the ability to imagine other ways to solve the problem of "crime." One of the interesting contributions of prison abolitionists has been to propose other paradigms of punishment or to suggest that we need to extricate ourselves from the assumption that punishment must be a necessary response to all violations of the law. Reconciliatory or restorative justice, for example, is presented by some abolitionists as an approach that has proved successful in non-Western societies -- Native American societies, for example -- and that can be tailored for use in urban contexts in cases that involve property and other offenses. The underlying idea is that in many cases, the reconciliation of offender and victim (including monetary compensation to the victim) is a much more progressive vision of justice than the social exile of the offender. This is only one example -- the point is that we will not be free to imagine other ways of addressing crime as long as we see the prison as a permanent fixture for dealing with all or most violations of the law.

Sunday, December 21, 2008

Hilda Solis Secretary of Labor

Obama appointed Hilda Solis, Democratic Rep from California's 32nd Congressional District (including East LA) as Secretary of Labor on Friday.

Prior to her election to Congress, Solis served eight years in the California state legislature, where she made history in 1994 by becoming the first Latina elected to the State Senate. In August 2000, Solis became the first woman to receive the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award for her pioneering work on environmental justice issues in California.

See her acceptance speech and thoughts on environmental justice here.

In 2003, Solis became the first Latina appointed to the powerful House Committee on Energy and Commerce where she is the Vice Chair of the Environment and Hazardous Materials Subcommittee and a member of the Health and Telecommunications Subcommittees.

The LA Times reports:

Elected to Congress in 2000 from a district that includes swaths of East L.A. and the San Gabriel Valley, Solis has consistently voted in support of labor's interests. A congressional voting analysis conducted by the AFL-CIO showed that she voted with organized labor 100% of the time last year.

She supported measures increasing the minimum wage, making it easier for workers to organize and preserving a ban on privatizing jobs at the Labor Department. Other labor groups that study congressional voting patterns gave her a 100% rating in 2005 and 2006.

J.P. Fielder, spokesman for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, suggested that Solis' voting record is overly weighted in labor's favor. "The business community recognizes that economic growth has happened in a number of non-unionized states. She has sided with the AFL-CIO in 97% of the votes that she has cast on the Hill," he said.

Solis also serves on the board of directors of American Rights at Work, which advocates for the right to form unions and bargain collectively. The chairman is former Rep. David Bonior of Michigan, who was also in the running for the Labor secretary post.

"I'm very excited," said Maria Elena Durazo, executive secretary-treasurer of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor. "This is an extraordinary moment for all women, but especially for the Latino community."

Durazo said Solis would be effective in the job because she is a "coalition-builder" who "doesn't walk in thinking everything has to be a battle with business."

Complete article here

Also, Affirmative Action Blog Spot reports that:

While Rep. Solis is most regarded for her environmental support, her record on civil rights is strong. She is rated 100% by the NAACP and reflects a "pro-affirmative action stance," according to the website "On the Issues." According to this site, Solis also voted:

YES on prohibiting job discrimination based on sexual orientation

NO on Constitutionally defining marriage as one-man-one-woman

Voted NO on making the PATRIOT Act permanent

Voted NO on Constitutional Amendment banning same-sex marriage

Co-sponsored a Constitutional Amendment for equal rights by gender

Rated 87% by the ACLU, indicating a pro-civil rights voting record

Issue a commemorative postage stamp of Rosa Parks

Co-sponsored the bill to Reinforce anti-discrimination and equal-pay requirements

http://www.ontheissues.org/CA/Hilda_Solis_Civil_Rights.htm

Sunday, December 14, 2008

Iranian-Canadian blogger missing for two months

Blogger Hossein Derakhshan missing in Iran

by Jerome Armstrong, Thu Dec 11, 2008 at 02:46:37 PM EST

Hossein Derakhshan is an Iranian-Canadian blogger that's widely considered the most well-known Iranian blogger. He's lived abroad, blogging in Canada, but recently went back to Iran on a visit. At some point shortly after his arrival in Iran, it is now being blogged, that he was arrested and jailed. The last post on his blog is from over two months ago. He's apparently been in jail for weeks, but the story just broke on a persian blog, which many have taken as a confirmation, and brought onto english on this blog:

Hossein has gone through various changes in his politics and he has rubbed many activists the wrong way, including myself. (I personally don't approve his politics and we have had couple of fierce arguments and fights in the past few months.) However, we should not have double standards when we deal with human rights. Any human being should be entitled to freedom of expression and should have access to an attorney while in jail. I hope human rights advocates start campaigning for Hossein Derakhshan.

Update: I personally talked to his sister, too. She is very worried about Hossein. We should be careful with the way we spread the news not to have a negative effect. Absolutely no neocon propaganda shit.

Saturday, December 13, 2008

Obama's cousin-in-law Rabbi Capers Funnye battles to open the gates of Judaism

Obama's cousin-in-law Rabbi Capers Funnye battles to open the gates of Judaism

By Julie Gruenbaum Fax, November 28, 2008, The Jewish Journal

Rabbi Capers C. Funnye Jr. is a kippah-wearing black rabbi who leads a multiethnic congregation in Chicago.

But if you happen to run into him, don't let your curiosity come across the wrong way.

Speaking last week in Los Angeles to an interdenominational group of rabbis who perform conversions, Funnye (pronounced fuh-NAY) described one of many unsettling encounters he's had in his 30-plus years as a Jew.

While visiting Florida about 10 years ago, Funnye attended morning prayers, donning his prayer shawl and tefillin. At the end of prayers, a man approached him.

"Are you Jewish?"

Funnye, with good-natured sarcasm, responded:

"Jewish? Nooooo. I was just walking by, and I saw this stuff just sitting there outside, and I wanted to see how it worked."

Funnye, 56, has dedicated his life to chiseling away at the conventional, but increasingly inaccurate, conception of who is a Jew. Whether by reaching out to Chicago's rabbis to allow him to serve on the board of rabbis or traveling to Nigeria to help the Ibo tribes explore their Jewish reawakening, Funnye is laying the groundwork for a time when the wider Jewish community can without questioning accommodate Jews of all ethnicities.

"I have to have one pair of glasses for all Jews and not see that because Jews are of a different ethnicity, that makes a difference in my approach to them," Funnye said. "I am working for the day that Jews are simply Jews."

That message resonated with the 35 rabbis gathered at Valley Beth Shalom in Encino for a daylong seminar of the Sandra Caplan Community Bet Din of Southern California, sponsored jointly with the Board of Rabbis of Southern California.

The Sandra Caplan Bet Din is a cooperative effort by Conservative, Reconstructionist and Reform rabbis to make the conversion process unified, warm and spiritually and psychologically meaningful.

Since it opened in 2002, the bet din has converted 122 people.

Funnye embodies in one person's journey all that these rabbis are working toward and struggling with: the need to break down false barriers in how "Jew" is defined; the challenge to wholeheartedly integrate those who convert; and the questions of self-definition that inevitably come up for born Jews, who are so often less knowledgeable and spiritually committed than apparent "foreigners" who choose to be Jewish.

"How we relate to the Jew-by-choice, the unchurched, the seekers, tells me more about myself than anything else," said Rabbi Harold Schulweis, rabbi at Valley Beth Shalom, who followed Funnye's keynote with a response. "When I look into the eyes of a Jew-by-choice, I see myself reflected."

In the past several decades, the topic of conversion has pitted liberal rabbis against their Orthodox counterparts, who don't recognize non-Orthodox conversions as legitimate. The issue is especially heated in Israel, where the Orthodox rabbinate holds legal status in civil affairs, such as marriage, divorce and burial.

But the rabbis at the seminar also expressed frustration at their own liberal members who refer to peers as "converts," even years after they've become Jewish.

Funnye himself converted three times. The first two times were with communities of black Jews -- also called Israelites or Black Hebrews.

Funnye's spiritual search began when his African Methodist Episcopalian minister advised him to think about going into the service of God. Christian tenets -- and especially the demands on its leaders -- didn't sit well with him. He explored Islam and evangelical Christianity while a student at Howard University, then a few years later, while working at Arthur Anderson consulting, he ran into a group of African Americans who wore kippahs. He began studying with them and attending their Chicago synagogue and converted to Judaism with that congregation in 1972, immersing in a pool.

It was a few years later that he attended a synagogue in Harlem, where he saw a fuller expression of Judaism and ritual, and the leader there encouraged him to become a religious leader for black Jews. In 1979 he re-immersed in a lake, since conversion requires immersion in a natural body of water or a mikvah, ritual bath. In 1985, after studying for four years, he was ordained by the New York-based Israelite Board of Rabbis. During that time, he also received his bachelor's and master's degrees from the Spertus Institute for Jewish Studies in Chicago.

And it was that year that he also decided he wanted a full, halachic conversion, one that would meet most mainstream Jewish legal standards. He put together a bet din of two Orthodox rabbis and two Conservative rabbis, including his mentor, Rabbi Morris Fishman. Funnye, his wife, Mary, and their four children -- who were already in Conservative day school at the time -- immersed in a mikvah.

Throughout his journey in the Jewish community, Funnye has recognized the need to make his community part of the fabric of the larger Jewish community.

Funnye is the rabbi of Temple Beth Shalom B'nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation, which serves a multiethnic population. Founded in 1918 and now with 220 members, the synagogue moved from Chicago's South Side to Marquette Park six years ago. Marquette Park is infamous as a center of activity for the American Nazi Party and site of a Martin Luther King Jr. march that ended after just a few blocks because bricks and bottles were being thrown.

Funnye has been at Beth Shalom since 1984, when he started as assistant rabbi. In 1991, he succeeded Rabbi Abihu Ben Reuben, who had led the congregation from 1947. While respecting Reuben's traditions and teachings, Funnye sought to give Judaism fuller expression in the services and rituals and to make the conversion process more oriented toward halachah, Jewish law.

At Funnye's congregation, Shabbat is an all-day event. Congregants come Friday night and then return Saturday for morning prayers, mostly in Hebrew, a reading of the entire Torah portion and an interactive sermon. A gospel-style choir brings congregants to their feet, and after a Kiddush lunch, about 70 percent of attendees stay for afternoon services and informal Torah study, followed by Havdalah.

Most of his congregants keep kosher, avoiding shellfish and pork, and buying kosher meat. Most of his members can't afford the high tuition of the day school but attend the congregation's Hebrew school.

Two of Funnye's sisters have also converted to Judaism, and his late mother regularly made sure her minister invited her son-the-rabbi to speak at church. Even his in-laws, religious evangelicals, are open to what they see as a way to draw closer to God. His two married children have both married Jews-by-choice. He and his wife have one granddaughter and six grandsons.

"I've told my children, 'If you don't marry someone who is Jewish, it is my prayer that they become Jewish. It doesn't matter to me what they look like. What matters to me is that they are Jewish, and their children are going to be Jewish, and that you instill in them and imbue in them the principals and values I have tried to instill and imbue in you,'" Funnye said, adding, "baruch Hashem (thank God) they've been listening to their old man."

He has many congregants who, like his family, have three generations or more at Beth Shalom. He also sees many spiritual seekers, among them white Jews. He is in the process of converting an extended Mexican family of anusim, Spanish Jews forced to convert to Christianity 500 years ago. The family was attracted to the synagogue because the worship space hidden in their family's Mexico City basement was also called Beth Shalom.

He teaches many seeking conversion and brings them before a bet din of Conservative rabbis -- one of the changes he made in an effort to up the quality of Jewish observance in his congregation. Potential converts must study for at least a year and attend services regularly.

"I often like to tell new people that when you start studying Judaism, every time you get a new book, every time you learn something new, it should feel like dipping a spoon into a bucket of fresh well water. If you ever had well water, it stimulates the whole being -- this is what Judaism does when we learn. It stimulates the being," Funnye said. "It's never stopped doing that for me. The more I learn, the richer it tastes; the better it tastes."

Funnye is vice president of the International Israelite Board of Rabbis, a group of 20 rabbis who serve five congregations in New York, one in Philadelphia, one in Chicago and one in Barbados.

Many black Jews believe that the original Israelites were African -- they came out of Egypt in North Africa -- and they consider themselves not converts, but reverts, going back to their true origins.

There is tremendous diversity among groups calling themselves Black Hebrew, Israelites or Black Jews. While some black Jewish congregations hew to Jewish theology and practice, others retain a messianic angle, including Jesus in their theology. Some have Jewish aspects but are mingled with many other traditions.

Funnye's adoption of halachic standards for his congregation stems in part from his desire to connect his flock with the mainstream Jewish community, something he has worked on for years.

After getting his degrees at Spertus, he worked as a business manager there until 1991. He not only got to meet Jewish luminaries, such as Elie Wiesel, but built relationships with many rabbis and professors.

He has touched many parts of the African American and Chicago Jewish communities: He has taught at congregational schools, he lectures widely, has consulted with the Spertus Museum of Judaica and the Du Sable Museum of African American History and has served on the boards of Chicago's Jewish Council on Urban Affairs, Akiba Schechter Jewish Day School and the Chicago Board of Rabbis.

Funnye's near-unanimous acceptance onto the board in 1997 held historical significance. His predecessors in New York, who had attempted to join their board of rabbis in the 1940s and '50s, did not even get dignified with a rejection -- they were simply ignored.

He also reaches out to the larger African American community through coalitions with neighborhood churches and has hosted joint programs with Muslim groups, as well.

Now, Funnye is extending that acceptance across the Atlantic to Africa.

Funnye is the associate director and Chicago regional director of BeChol Lashon, Hebrew for "in every language," an initiative of the San Francisco-based Institute for Jewish and Community Research (IJCR), where he is a senior researcher. The program reaches out to Jews of color from all over the world, from the anusim communities of Latin America to African tribes rediscovering Jewish roots, like the Abuyudaya of Uganda. Funnye is coordinator for IJCR's Pan-African Jewish Alliance, which seeks to connect African American Jews with Jews in Africa. Funnye has been to Africa six times and works primarily with the Ibo of Nigeria.

Ongoing research by the Pan-African Jewish Alliance has found that there may be as many as 30,000 Nigerians reclaiming Jewish roots. An Ibo oral tradition holds that their ancestors were Hebrews who migrated from Israel to Africa 1,500 years ago. While many have no trace of Jewish heritage, others have held on to traditions. The Ibo circumcise their boys on the eighth day and gather their elders by sounding teruah and shevarim notes on the ram's horn. Their priests wear a white garment with blue stripes, fringed all around. As the Ibo begin to explore their Jewish roots and try to connect to the worldwide Jewish community, Funnye's congregation is raising funds to build a sister synagogue in Nigeria, and he is working to get the Ibo the educational materials and leadership they need.

"Africa is ripe with hundreds, even thousands of people who claim a link to Judaism, and they're asking the question, 'Where is the gate that leads to Jewish peoplehood?'"

Funnye wants the answer to that question to resonate a little more loudly and clearly.

He understands that most American Jews still aren't used to Jews of color, but he is convinced that as more people around the world discover and explore either their ancient Jewish roots or their dormant Jewish spirit, the wider Jewish community will begin to take seriously the words of Isaiah: "My house shall be called a house of prayer for all nations."

"I believe those biblical prophecies are going to have more people reaching out and searching and going on spiritual journeys, and, ultimately, Judaism is going to be a place they want to examine and investigate. I only hope and pray that the gates to our synagogues are open and welcoming."

At the seminar in Encino last week, Valley Beth Shalom's Schulweis cautioned that to move forward, rabbis must acknowledge the sometimes dominant strain in Jewish tradition that holds a deep suspicion of conversion.

But, he said, Jewish texts and history have an equally strong tradition of welcoming the proselyte, and it is that tradition the seminar explored and pushed forward.

The rabbis shared best practices, studied relevant texts and explored innovative ways of making all aspects of conversion deeply spiritual and uplifting, not just for the people converting but for everyone around them.

The Sandra Caplan Bet Din's meshing of divergent streams of Judaism -- a collaboration that took several years to negotiate -- augers well for the more expansive bridges Funnye and the Los Angeles rabbis are trying to build.

"The remarkable thing about Los Angeles is we have colleagues who like each other, respect each other and are willing to talk to each other," said Rabbi Stewart Vogel, president of the Board of Rabbis of Southern California, an interdenominational umbrella group. "When you can engage in dialogue, anything can happen. We can get past stereotypes and prejudices, and we can work together to create the Jewish community we want."

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Mass graves in Afghanistan

McClatchy: U.S. Kept Silent About Afghan Mass Grave Removal

by Meteor Blades

Thu Dec 11, 2008 at 03:29:18 PM PST

Tom Lasseter at McClatchy is reporting an important story about how U.S. officials have failed to notice the digging up of a mass grave of perhaps 2000 prisoners of war in Afghanistan. The excavation removed evidence of a possible war crime. What U.S. officials knew, and whether they may have been involved in any way in covering up the removal of bodies from the grave, is unknown.

Seven years ago, a convoy of container trucks rumbled across northern Afghanistan loaded with the human cargo of suspected Taliban and al Qaida members who'd surrendered to Gen. Abdul Rashid Dostum, an Afghan warlord and a key U.S. ally in ousting the Taliban regime.

When the trucks arrived at a prison in the town of Sheberghan, near Dostum's headquarters, they were filled with corpses. Most of the prisoners had suffocated, and others had been killed by bullets that Dostum's militiamen had fired into the metal containers.

Dostum's men hauled the bodies into the nearby desert and buried them in mass graves, according to Afghan human rights officials. By some estimates, 2,000 men were buried there.

Earlier this year, bulldozers and backhoes returned to the scene, reportedly exhumed the bones of many of the dead men and removed evidence of the atrocity to sites unknown. In the area where the mass graves once were, there now are gaping pits in the sands of the Dasht-e-Leili desert.

Farid Mutaqi, a senior investigator for the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, told McClatchy: "You can see only a hole. In the area around it you can find a few bones or some clothes. The site is gone . . . as for evidence, there is nothing."

Speculation by McClatchy sources is that this mass grave was excavated with heavy equipment so that Dostum could avoid prosecution for war crimes.

And U.S. involvement? The Cheney-Bush administration has been silent about the digging up of the grave. When the killings of the prisoners occurred in 2002, administration officials denied they knew about until it appeared in media reports.

However, the fact that U.S. special forces and CIA operatives were working closely with Dostum in late 2001, when the killings took place, has fueled suspicions that the warlord got a free pass.

The U.S. Defense Department has said that it found no evidence of American involvement or presence during the 2001 incident. If there was an investigation, however, its findings have never been made public.

In May 2002, a Physicians for Human Rights team dug a test trench in the area and uncovered 15 bodies, three of which were found to have died of asphyxiation. In November that year, in a top-secret cable from the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research, the number of people killed during prisoner was said to "approach 2,000."

In response to the McClatchy exposé, Frank Donaghue, CEO of Physicians for Human Rights, said:

Investigative reports by McClatchy newspapers, as well as PHR’s own findings, have revealed that large sections of the Dasht-e-Leili mass grave in Northern Afghanistan have been dug up and removed.

PHR discovered this grave site in 2001. Reportedly, this site may have contained the bodies of as many as 2,000 prisoners who surrendered to the forces of Afghan warlord, General Abdul Rasheed Dostum and US commandoes in November 2001.

For seven years PHR has been investigating allegations that these prisoners were suffocated in cargo containers and dumped in the desert.

Reportedly, this evidence of potential war crimes was removed during the past year by the forces of General Dostum.

Our efforts on this case have involved PHR’s International Forensic Program, which has documented human rights violations and mass atrocities around the world.

PHR investigators discovered this mass grave in 2002, as reported in a Newsweek magazine special report. Our forensic scientists conducted an initial assessment of the grave for the UN and performed preliminary autopsies of several bodies at the site.

Since 2001, PHR advocated for the site to be secured and for a full investigation to be conducted by the US, the United Nations, and the Government of Afghanistan.

Now, in the wake of these revelations of the destruction of the grave site, PHR is calling on Afghan President Karzai and the United Nations to ensure that any remaining evidence at the site be secured.

The additional revelations by McClatchy newspapers, as well as documents, which PHR received this year under the Freedom of Information Act indicate that the Bush Administration blocked internal investigations into this alleged war crime.

Congress must hold a full, public inquiry into what the Bush Administration knew about these events and what they did or did not do about it. It’s time for truth and accountability, and a restoration of the rule of law. Respect for human rights demands nothing less.

Indeed so. Respect for human rights and the rule of law do demand nothing less.

Dostum, who has denied reports over the past few days that he is seeking asylum in Turkey, has a long and nasty record that has failed to stop U.S. officials from working with him. That makes him worthy of investigation aside from the mass graves story. For instance, Time reported on December 9:

Last year Samimi received a phone call from General Abdul Rashid Dostum, a U.S. ally who was appointed by Afghan President Hamid Karzai as Army Chief of Staff, threatening to have her raped "by 100 men" if she continued investigating a rape case in which he was implicated. Dostum denies ever making such a threat and calls the rape allegation "propaganda." A witness to the phone call, military prosecutor General Habibullah Qasemi, was dismissed from his post soon after, despite carrying a sheaf of glowing recommendation letters penned by U.S. military supervisors.

Links to documents about Dasht-e-Leili that the Physicians for Human Rights acquired via the Freedom of Information Act are here and here.

PHR also has an Afghan resource site with information about the mass grave war crimes investigation here.

Show the World What Racial Justice Looks Like

CALL FOR POSTERS

Submissions are due by midnight, Monday, January 5, 2009

One submission will be selected for reproduction as a poster that will

be provided at no cost to community organizations, foundations, and

other allies. The artwork may also be reproduced on other Akonadi

public education materials, such as a commemorative card. All submis-

sions will be featured on the Akonadi Foundation website. The artist

selected will receive a $1,000 prize that includes $500 for the artist

and $500 as a donation to the Oakland community organization

designated by the artist.

SELECTION CRITERIA

Selection of artwork will be based on: creativity and originality, and

artistic and design quality, and potential to inspire and inform racial

justice movement building.

Selection will be made by

*Quinn Delaney, Akonadi Foundation founder and Board Chair

*Juan Fuentes, artist/former director of Mision Grafica

*Mateo Nube, Director, Movement Generation

*Mervyn Mercano, Training Director, Center for Media Justice

SUBMISSION GUIDELINES

Poster submissions must focus on racial justice movement building in

Oakland or the Bay Area. Submissions must include a visual image

accompanied by words conveying the theme. All artwork must be

original. Artists must have permission to use any copyrighted images

displayed in the artwork. The artist’s name should not appear on the

artwork for the purposes of judging. The final dimensions of the poster

will be 11 x 17 (please keep this in mind as you execute your design).

Artwork must be submitted as a jpeg attachments, high resolution (300

dpi), to info@akonadi.org or as hard copy photo ready art.

Artists must include a completed submission form. Download here.

Hardcopy art can be submitted to the foundation at:

Akonadi Foundation

ATTN: RACIAL JUSTICE POSTER PROJECT

436 14th Street, Suite 1417

Oakland, CA 94612

Sunday, December 7, 2008

Thousand Kites Phone Calls

Join the ninth annual CALLS FROM HOME radio broadcast for prisoners.

The United States has 2.4 million people behind bars. Thousand Kites wants you to lend your voice to a powerful grassroots radio broadcast that reaches into our nation's prison and lets those inside know they are not forgotten.

We are asking you to call our toll-free line 877-518-0606 and speak directly to those behind bars this holiday season. (An answering machine will record your message) Read a poem, sing a song, or just speak directly from you heart. Speak to someone you know or to everyone---make it uplifting.

So call right now at 877-518-0606. We will post each call on our website as it comes in! Check our website www.thousandkites.org to listen to your call and others!

CALLS FROM HOME will broadcast on over 200 radio stations across the country and be available for download from our website on December 13.

Call anytime (now through December 9) at 877-518-0606 and record your message.

Learn how you can help blog, distribute, broadcast, or support this event.

CALLS FROM HOME is a project of Thousand Kites/WMMT-FM/Appalshop and a national network of grassroots organizations working for criminal justice reform.

Actions Speak Louder

http://anarchymo.wordpress.com/2008/12/05/help-stop-immigrant-detention-center-in-farmville/

From the site:

So, the Town of Farmville and a private company called Immigrant Centers of America are trying to build a 1,000 bed immigrant detention center in Farmville. ICA has zero experience with prisons or detention centers. Their previous experience is constructing Arby’s and BP Gas stations. This project has already received over 500,000 dollars from the State Tobacco Commission. This is not a done deal, the project can still, and will be stopped.

You can help stop it by sending an email to some of the folks involved, letting them know you think it is a bad idea. I’ve put a list of emails below, that includes people on town council, people from the VA Tobacco Comission, people from DHS, and people who run ICA.

They have pre-written letters and the email addresses of folks to send it to - super easy, can make an impact.. not a tough decision, folks.

GREECE LIGHTNING

Hunger strike ends as Greek government caves

> Thursday, November 20 2008 @ 11:36 PM CST

> Contributed by: WorkerFreedom

>

> After 18 days 7,000 prisoners in greece stop their hunger strike after the

> ministry of justice concedes to a series of their demands, promising to

> release half the country's prison population by April 2009.

>

> On Thursday the 20th of November more than 7,000 hunger strikers in greek

> prisons demanding a comprehensive 45-point program of prison reform have

> decided to stop their hunger strike, already on its 18th day, after the

> Ministry of Justice responded to their struggle and to the widening

> solidarity movement which in the last weeks has held several mass protest

> marches in the greek cities by declaring that by next April the number of

> prisoners in greek jails will be reduced to 6.815 from the present 12.315,

> thus effectively releasing half of the country's prison population.

>

>

>

> The Ministry's declaration in detail states that:

>

> 1) All persons convicted to a sentence up to five years for any offense

> including drug related crimes can tranform their sentence into a monetary

> penalty. This will not be allowed in the case the jury decides that the

> payment is not enough to deter the convict from commiting punishable acts

> in the future.

> 2) The minimum sum for tranforming one day of prison sentence to monetary

> penanlty is reduced from 10 euros to 3, with the provision of being

> reduced to 1 euro by decision of the jury.

> 3) All people who have served 1/5 of their prison sentence for 2 year

> sentences and 1/3 for sentences longer than 2 years are to be released,

> with no exceptions.

> 4) The minimum limit of served sentence is reduced to 3/5 for conditional

> release and for convicts for drug related crimes. Those condemned under

> conditions of law Ν. 3459/2006 (articles 23 και

> 23Α) are excepmpted.

> 5) The maximum limit of pre-trial impironment is reduced from 18 to 12

> months, with the excemption of crimes puniched by liife or 20year

> sentence.

> 6) The annual time of days-off prison is increased by one day. Tougher

> conditions for days-off are limited for those convicted for drug related

> crimes under Ν. 3459/2006.

> 7) Disciplinary penalties are to be integrated.

> 8) Integration after 4 years into national law of the European Council

> decision of drug trafficking (2004/757).

> 9) Expansion of implementation of conditional release of convicts

> suffering from AIDS, kidney failure, persistent TB, and tetraplegics.

> What the Ministry failed to answer with regard to the prisoners' demands

> include:

> 1) Monetary exchange of prison sentences longer than 5 years, especially

> for 6.700 prisoners presently convicted for non-criminal offenses.

> 2) Abolition of juvenile prisons

> 3) Abolition of accumulative disciplinary penalties

> 4) Abolition of 18 months pre-trial imprisonment for a large number of

> offenses.

> 5) Satisfactory expansion of days off, despite the fact that the

> application of present liberties has been tested as succesfull during the

> last 18 years.

> 6) Immediate improvement of relocation conditions of convicts

> 7) Holding a meeting between the minister of justice and the prisoners'

> committee

>

> Thus in a press release, the Prisoners' Commitee announced that:

>

> "The amendment submitted to the Parliament by the Ministry of Justice

> tackles but a few of our demands. The minister ought to materialize his

> promises for the immediate release of the suggested number of prisoners

> announced, and at the same time implement concrete measures regarding the

> totality of our demands. We the prisoners treat this amendment as a first

> step, a result of our struggle and of the solidarity shown by society. Yet

> it fails to covers us, it fails to solve our problems. With our struggle,

> we have first of all fought for our dignity. And this dignity we cannot

> offer as a present to no minister, to no screw. We shall tolerate no

> arbitrary acts, no vengeful relocation, no terrorizing disciplinary act.

> We are standing and we shall stay standing. We demand form the Parliament

> to move towards a complete abolition of the limit of 4/5 of served

> sentence, the abolition of accumulated time for disciplinary penalties,

> and the expansion of beneficial arrangements regardi

> ng days-off, and conditional releases for all categories of prisoners.

> Moreover, we demand the immediate legislation on the presently vague

> promises of the minister of justice regarding the improvement of prison

> conditions (abolition of juvenile prisons, foundation of therapeutic

> centers for drug dependents, implementation of social labour in exchange

> for prison sentence, upgrading of hospital care of prisoners,

> incorporation of european legislation favorable to the prisoners in the

> greek law etc.). Finally, we offer our thanks to the solidarity movement,

> to every component, party, medium, and militant who stood by us with all

> and any means of his or her choice, and we declare that our struggle

> against these human refuse dumps and for the victory of all our demands

> continues".

> Prisoners' Committee 20/11/08.

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

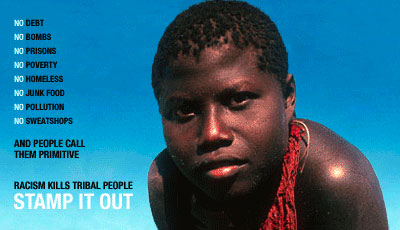

STAMP IT OUT!

Saturday, November 22, 2008

Dave Stein's link took me here

Dylan Rodriguez is not only a warm, wonderful person, but he is also absolutely brilliant. This piece made me think a lot so I wanted to share it - it is from RaceWire's archives - I always find that when I try to spend five minutes there I usually end up reading for at least an hour. I'd love to hear thoughts!

The Dreadful Genius of the Obama Moment

Inaugurating Multiculturalist White Supremacy

By Dylan Rodríguez

What happens to the politics of antiracism when the phenotype of white

supremacy “changes?” At the risk of being scolded for offending the

optimistic spirit of this historical moment, I offer these thoughts

with a different kind of hope: that the spectacle and animus of the

Obama campaign, election, and presidency fail, and fail decisively, to

domesticate, discipline, and contain a politics of radical opposition

to a U.S. nation-building project that now insists on the diversity of

the American “we,” while leaving so many for dead.

To be clear: the political work of liberation from racist state

violence—and everything it sanctions and endorses, from premature

death to poverty—becomes more complex, contradictory, and difficult

now. The dreadful genius of the multiculturalist Obama moment is that

it installs a "new" representative figure of the United States that,

in turn, opens "new" possibilities for history's slaves, savages, and

colonized to more fully identify with the same nation-building project

that requires the neutralization, domestication, and strategic

elimination of declared aliens, enemies, and criminals. In this

sense, I am less anxious about the future of the "Obama

administration" (whose policy blueprint is and will be relatively

unsurprising) than I am about the speed and effectiveness with which

it has rallied the sentimentality and political investment (often in

terms of actual dollar contributions and voluntary labor) of the

purported U.S. "Left."

Celebratory liberal multiculturalist patriotism, in whatever complex

and historically laden form it assumes, is a deadly compromise. I

recognize, with all due respect, that millions are moved to tears as

they recognize in Obama the promise of a fulfilled democratic

(Black/multicultural) citizenship—the national fraud that millions

have bled, died, and cried over, before and beyond the Civil Rights

Movement—while weeping joyfully at the possibility of (their children

and grandchildren) finally becoming human in a place that seems

obsessed with destroying, dehumanizing, and humiliating.

Living in a history of racism, genocide, and everyday suffering is a

heavy thing, and moments of optimism are preciously rare. This is why

the historical burden is multiplied for those who care to address the

euphoria with a different kind of urgency: to move against the

visceral sentimentality of the moment and insist, over and over again,

that optimism endorses terror when its premises are removed from—and

therefore unaccountable to—liberation struggle in all its wonderful

forms. It is worth restating that the historical point of departure

for liberation politics is uncompromising opposition to a

racist/colonialist/imperialist state (regardless of who leads it), and

a willingness to pursue wild but principled ambitions for the sake of

achieving the political fantasy of radical freedom. Herein, the

pending inauguration of an authentically multiculturalist white

supremacy entails, at best, a change of leadership for a mind-numbing

apparatus of normalized repression and mass-based social violence, the

one that capably imprisons well over 2.5 million people (most of them

poor, Black, and Brown) in cages all over the world and will kill well

over 2 million Iraqi, Afghanis and Palestinian civilians (through a

combination of blockades, bombs, and "diplomacy") in the span of less

than a generation. This apparatus is the one thing that will not

change, even as some entrust the Obama administration with the

arrogant hopes of a reduced global body count.

Putting aside, for the moment, the liberal valorization of Obama as

the less-bad or (misnamed) "progressive" alternative to the horrible

specter of a Bush-McCain national inheritance, we must come to terms

with the inevitability of the Obama administration as a refurbishing,

not an interruption or abolition, of the normalized violence of the

American national project. To the extent that the subjection of

indigenous, Black, and Brown people to regimes of displacement and

suffering remains the condition of possibility for the reproduction

(or even the reinvigoration) of an otherwise eroding American global

dominance, the figure of Obama represents a new inhabitation of white

supremacy's structuring logics of violence.

This is to say, Obama's ascendancy hallmarks the obsolescence of

"classical" white supremacy as a model of dominance based on white

bodily monopoly, and celebrates the emergence of a sophisticated,

flexible, "diverse" (or neoliberal) white supremacy as the heartbeat

of the American national form. The signature of the "post-civil

rights" period is precisely marked by such changes—compulsory and

voluntary—in the comportment, culture, and workforce of white

supremacist institutions: selective elements of police and military

forces, global corporations, and major research universities are

diversely colored, while their marching orders continue to mobilize

the familiar labors of death-making (arrest and justifiable homicide,

fatal peacekeeping, overfunded weapons research, etc.). While the

phenotype of white supremacy changes—and change it must, if it is to

remain viable under changed historical conditions—its internal

coherence as a socialized logic of violence and dominance is sustained

and redeemed.

Candidate Barack Obama's "A More Perfect Union" speech, arguably the

definitive moment of his campaign for the U.S. presidency, provides a

useful elaboration of this change in the political structure of white

supremacy. Given that this was one of the few moments in the campaign

in which Obama actually addressed "race" as a political issue rather

than a descriptive matter-of-fact, a close attention to the oration

reveals something about the premises of the new multiculturalist,

nationalist optimism. Lifting its title from the opening sentence of

the U.S. Constitution, Obama's denunciation of Chicago pastor and

Black liberation theologian Jeremiah Wright begins with a backhanded

caricature of racial chattel slavery that replicates the classical

liberal denial of the nation's constitutive—in fact

Constitutional—patriarchal white supremacist conditions of

possibility:

"The document [the nation's founders] produced was eventually signed

but ultimately unfinished. It was stained by this nation's original

sin of slavery, a question that divided the colonies and brought the

convention to a stalemate until the founders chose to allow the slave

trade to continue for at least twenty more years, and to leave any

final resolution to future generations."

Obama's condemnation of "original sin" begets the white Christian

nation's perpetual forgiveness and redemption, but also anticipates

the pessimism of those who would rightfully allege that white

supremacy's visceral structures of dominance are endemic to American

national reproduction. This attempts to erase the indelible: the

social and economic system that rests on the subjection of Africans as

racial chattel is not a compartmentalized or reconcilable event in the

American white racial destiny, but is the foundation of what legal

scholar Cheryl Harris has called the ongoing legal consolidation of

whiteness as property, a consolidation that can only occur at the

expense of those who are dispossessed and/or actually owned by the

white nation.

Thus, while Obama's otherwise stale re-narration of white supremacist

nation-building falls back on an allegory of the sinning-forgiven

white body politic, his comportment of "electability" proposes an

authoritative black/multiracial/multicultural patriotism that

rejuvenates the rhetorical matrix of contemporary white supremacy. He

is "presidential" precisely because he galvanizes admiration and

reverence through a paean to the historical imagination of the white

slaveholding nation. Obama fetishizes racist/slave "democracy" as a

piece of the American national mythology, a moral tale of vindication

that alleviates the white nation's guilty burdens of the racial

present. More importantly, it permanently defers the political

obligation of confronting an enduring and present white supremacist

social form.

"Of course, the answer to the slavery question was already embedded

within our Constitution—a Constitution that had at its very core the

ideal of equal citizenship under the law; a Constitution that promised

its people liberty, and justice, and a union that could be and should

be perfected over time."

A vast and deep body of scholarly critique and radical social thought

has thoroughly refuted the common sense of the U.S. Constitution as a

magical and morally transcendent document that has timelessly valued

the "ideal of equal citizenship" within its philosophical

architecture. In fact, the most incisive critical race theorists

argue that the opposite is closer to the historical truth: it is the

ongoing racial-national project of determining which aliens and

nominal "citizens" are to be marginalized and excluded from the

entitlements of citizenship that sits at the heart of the

Constitution. Why, then, does the political integrity of Obama's

"race speech" rest on the foundations of such a flimsy, hackneyed

sense of history?

The genius of Obama's oration is not traceable to its racially marked

(and rather overstated) "eloquence" or any substantively original

content: rather, its profound resonance with a liberal

white/multiculturalist sensibility derives from the fact that it is an

authoritative 21st century doctrine of the "color line," a deforming

of the early 20th century DuBoisian wisdom that "the problem of the

Twentieth century is the problem of the color line," and "the social

problem of the twentieth century is to be the relation of the

civilized world to the dark races of mankind."

"On one end of the spectrum, we've heard the implication that my

candidacy is somehow an exercise in affirmative action; that it's

based solely on the desire of wide-eyed liberals to purchase racial

reconciliation on the cheap. On the other end, we've heard my former

pastor, Reverend Jeremiah Wright, use incendiary language to express

views that have the potential not only to widen the racial divide, but

views that denigrate both the greatness and the goodness of our

nation; that rightly offend white and black alike."

While for DuBois, the color line would be understood as a primary site

of political antagonism in the emergent "American Century," Obama

posits the contemporary color line—his "racial divide"—as the terrain

of the American nation's neoliberal, post-civil rights perfection, the

culmination of its progressive national telos, and the place of

fulfillment for an authentic national culture of "unity." In this

context, his disavowal of Rev. Wright not only marked Obama's

electoral phobia of Black liberationist political affinities, it

clearly pronounced his solidarity with a liberal racist consensus:

"[Wright's comments] expressed a profoundly distorted view of this

country—a view that sees white racism as endemic, and that elevates

what is wrong with America above all that we know is right with

America; a view that sees the conflicts in the Middle East as rooted

primarily in the actions of stalwart allies like Israel, instead of

emanating from the perverse and hateful ideologies of radical Islam.

"As such, Reverend Wright's comments were not only wrong but divisive,

divisive at a time when we need unity; racially charged at a time when

we need to come together to solve a set of monumental problems—two

wars, a terrorist threat, a falling economy, a chronic health care

crisis and potentially devastating climate change; problems that are

neither black or white or Latino or Asian, but rather problems that

confront us all."

At the risk of some oversimplification, the political logic is clear:

some lives and destinies matter dearly, while others must be

neutralized, disciplined, or decisively ended; radical antiracism and

liberationist struggle are the bane of national unity, and can only

disturb the seamless progress of the diverse nation toward resolution

of its "monumental problems."

"This is the political condition of possibility for the opening lines

of the victory speech that arrived in storybook fashion just days ago:

If there is anyone out there who still doubts that America is a place

where all things are possible, who still wonders if the dream of our

founders is alive in our time, who still questions the power of our

democracy, tonight is your answer."

The euphoria of the moment allowed far too many to happily surrender

any political and moral revulsion at this invocation of the Founding

Fathers, and pushed far too few to seriously consider what, exactly,

animated the founders' nation-building dream and what it might mean

for someone like Obama to valorize it. In the end, however, my

concern is not with Barack Obama the politician, but rather with the

emerging liberal multiculturalist common sense that assembles its

points of optimistic compromise and political enthusiasm in alliance

with the reforming and re-visioning of classical white supremacy that

the Obama campaign and administration represent.

While the historical trajectory and political structure of U.S. white

supremacist nation-building will not be substantively altered, its

explanatory rhetoric, institutional appearance, and resurfaced racial

personage has generated a sweeping political sentimentality and

popular cultural narrative of progress, hope, change, and racially

marked nationalist optimism. And what do these things mean, really,

in the age of Katrina, the prison industrial complex, and the War on

Terror?

At best, when the U.S. nation building project is not actually engaged

in genocidal, semi-genocidal, and proto-genocidal institutional and

military practices against the weakest, poorest, and darkest—at home

and abroad—it massages and soothes the worst of its violence with

banal gestures of genocide management. As these words are being

written, Obama and his advisors are engaged in intensive high-level

meetings with the Bush administration's national security experts.

The life chances of millions are literally being classified and

encoded in portfolios and flash drives, traded across conference

tables as the election night hangover subsides. For those whose

political identifications demand an end to this historical conspiracy

of violence, and whose social dreams are tied to the abolition of the

U.S. nation building project's changing and shifting (but durable and

indelible) attachments to the logic of genocide, this historical

moment calls for an amplified, urgent, and radical critical

sensibility, not a multiplication of white supremacy's "hope."

Welcome to my blog!

"Dance," said the Sheep Man. "Yougottadance. Aslongasthemusicplays. Yougottadance. Don'teventhikwhy. Starttothink, yourfeetstop. Yourfeetstop, wegetstuck. Wegetstuck, you'restuck. Sodon'tpayanymind, nomatterhowdumb. Yougottakeepthestep. Yougottalimberup. Yougottaloosenwhatyoubolteddown. Yougottauseallyougot. Weknowyou'retired, tiredandscared. Happenstoeveryone, okay? Justdon'tletyourfeetstop."

"Dancingiseverything," continued the Sheep Man. Danceintip-topform. Dancesoitallkeepsspinning. Ifyoudothat, wemightbeabletodosomethingforyou. Yougottadance. Aslongasthemusicplays."